- Admission

- Discover Episcopal

- Our Program

- Athletics

- Arts

- Spirituality

- Student Life

- Support Episcopal

- Alumni

- Parent Support

- Knightly News

- Contact Us

- Calendar

- School Store

- Lunch Menu

- Summer Camps

« Back

Let's Embrace and Not Erase Immigrant Heritage Languages

November 9th, 2023

LAUNCH 2024 will be held on Friday, March 8, and feature a number of presentations by Episcopal students who have spent significant time on a special project. In this series, we will share short articles related to LAUNCH presenters’ topics as a way to foreshadow the many amazing projects and ideas you will see on LAUNCH day.

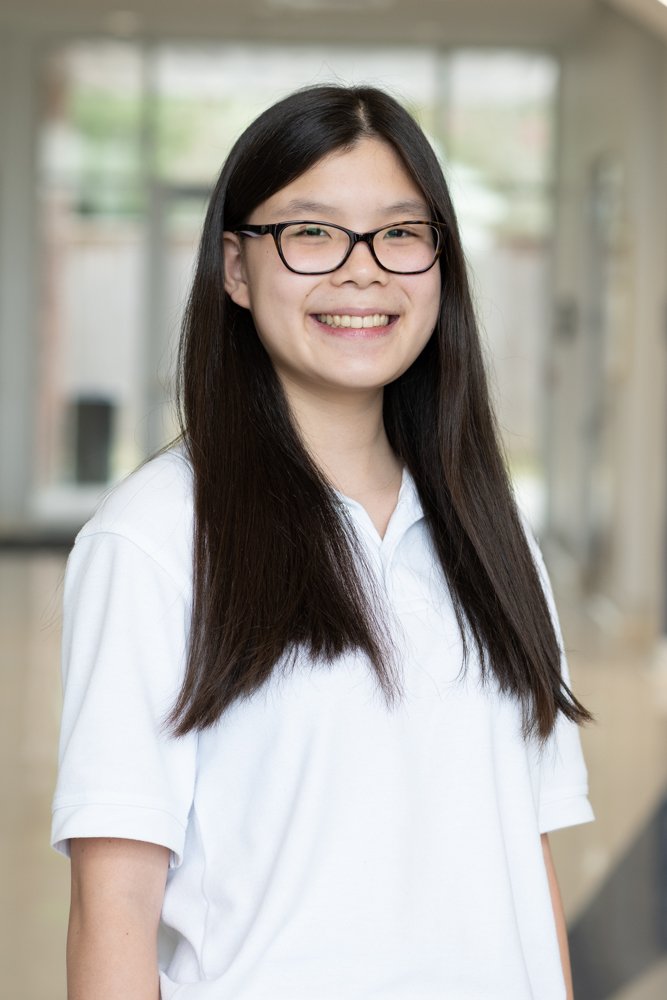

Our next article is by Thesis student Kathy Hu who explores the lives and schooling of immigrant children in America. Her thesis weaves her own personal narrative, interviews and scholarship to tell a complete story of what can be lost when children of immigrants are encouraged to leave their family’s language behind in an attempt to assimilate fully.

Every day after school, I pad my way down the green hill toward the carpool line, where I see my dad’s car patiently awaiting me. He sits inside, his phone blaring Chinese from an old pop ballad I recognize or the Chinese drama he watches. He looks up as I open the car door, asking me how my school day was. I reply with the usual “good” and relay funny moments that happened in class to my dad, who, despite his gruff exterior, loves to gossip. But no one will ever be able to listen in because the words flying around in the car are in Chinese.

I’ve grown up in a Chinese-speaking household and have been able to procure the language, claiming it as one of my own. I wake up and exchange morning pleasantries with my dad in Chinese before switching to English at school and returning home to a delicious waft of Chinese food in the evening. However, as I look outside of my family’s bubble, the sad reality is that many immigrant children lose their heritage languages because of the pressure to assimilate into traditional American society that exists to this day.

Until the 1960s, much of the research around bilingualism and its effect on intelligence revealed a negative relationship, leading to harmful American opinions of bilingualism. Supported by now-defunct scientific studies, some Americans projected these biased attitudes onto immigrant parents who viewed speaking only English and becoming “American” as the sole way to help their children succeed. With such a drastic linguistic and cultural change, immigrant families grew distant across generations. Without a common language uniting a family, children cannot ask for help, tell stories, or learn about their culture. Most immigrant children are limited to primary phrases, such as “How was your day?” or “What’s for dinner?” especially if their parents are not entirely fluent in English. Such a situation can lead to feelings of isolation and detachment for some immigrant children who do not have their families to turn to.

However, that isolation subsided after the 1960s as the benefits of multilingualism surfaced, and society’s perception of language changed in favor of heritage languages. Nowadays, it might seem easy for immigrant parents to stop worrying and pass down their heritage or native language to their children, but American mistreatment still exists. Countless instances of people berating immigrants for speaking their native language prove that some Americans still believe speaking a language other than English is “un-American.” Some also treat English proficiency as “cultural capital,” where those more skilled in English are at the top of the “social hierarchy,” and those who struggle with English are at the bottom.

Mainstream society needs to change this mindset and allow immigrant children to learn their heritage languages without being burdened by what society might think. There’s much to explore with a heritage language, whether through music, food, or TV shows, and knowing a different language can unlock many doors. Instead of assimilating into the “melting pot” America is famous for, immigrant families should be able to retain their cultures and languages. So, rather than a melting pot, let’s view America as a salad bowl instead.

My parents represent a small sliver of immigrants who have settled in the US, but their emphasis on me learning Chinese has helped me in ways I could never have imagined.

When I was younger, I attended Chinese school, and I remember vehemently protesting against going. The two hours we would spend every Sunday rereading the same passages were the epitome of monotony and boredom. As I repeatedly tried to quit, my mom always responded: “You cannot quit Chinese school. You’ll thank me later for this.” I had thought then: No, I will never look back at this time with fondness.

Yet, I do. In hindsight, I wish I had paid more attention to absorbing the Chinese characters we would study instead of memorizing them the night before (and quickly forgetting them the day after). Despite my weekly grumblings, I was proud to graduate as a member of the 8th-grade class, and in the end, I was thankful that Chinese school forced me to keep in touch with the written Chinese language. It allows me to text in Chinese on WeChat and feel connected to all the scrumptious delicacies and rich traditions my culture brings.

Episcopal makes sure to promote and appreciate the different cultural traditions their students celebrate through various endeavors. This year, I was pleasantly surprised to learn of the creation of an Asian Heritage Club in addition to a preexisting African Heritage Club; our first meeting was one of the highlights of my first quarter! I snacked on delicious mooncakes – in time for the Mid-Autumn Festival – and learned about the holiday alongside other interested students in the Upper School. Over in Lower School, students were also celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival with a visit from Taiwanese-American children's writer and illustrator Grace Lin along with a special bento box lunch and Chinese-influenced crafts. Even during the spring, I always spot colorful children walking around campus after the Lower and Middle Schools celebrate Holi by tossing vibrant colors. Soon, we will also have foreign exchange students from Chile among us, experiencing what school is like in the United States while teaching us about their culture. Through all these events, Episcopal makes their students feel seen by celebrating their cultures with them, and as a Chinese-American Upper School student, I am deeply appreciative of this. I feel comfortable with my Chinese identity here at Episcopal and even get to tell my story through my LAUNCH presentation in March.

After learning about the multilingual struggle in the United States for my Thesis, I’ve become forever grateful to my parents. Despite the stress they must have felt raising me in the very monolingual US, they made sure to maintain the heritage language in our home so I could have the ability to connect with my Chinese identity. Without this language, I wouldn’t know who I am, and I wouldn’t ever experience the closeness I’ve developed with my parents. I want other immigrant children to have the same ability to learn their heritage language and experience the beauty that language can unlock in their lives.

Kathy Hu is a senior and has attended Episcopal for four years. She is the President of Mu Alpha Theta and Science Club, Co-President of Beta Club, and Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Troubadour Literary Magazine. She enjoys tutoring fellow students in the Academic Resource Center, popping in to create various art projects around school, and talking about books with the Society of Words book club. Outside of school, Kathy also plays clarinet and piano.

The Episcopal School of Baton Rouge 2025-2026 application is now available! For more information on the application process, to schedule a tour, or learn more about the private school, contact us at [email protected] or 225-755-2685.

Other articles to consider

Jun5Episcopal Announces New Athletic Director

Jun5Episcopal Announces New Athletic DirectorPlease join us in welcoming Brent Broussard to the Episcopal community.

See Details Jun2Episcopal Welcomes Dan Binder as the Next Upper School Division Head

Jun2Episcopal Welcomes Dan Binder as the Next Upper School Division HeadPlease join us in welcoming Dan Binder to the Episcopal community.

See Details May22End of the Year Reflection from Dr. Steakley

May22End of the Year Reflection from Dr. SteakleyAn Episcopal education and the community that supports it are remarkable. Dr. Steakley looks back at the moments that made the 2024/2025 school year.

See Details May12Tutoring with a Purpose: Jackson Ezell Reflects on His Time in the Academic Resource Center

May12Tutoring with a Purpose: Jackson Ezell Reflects on His Time in the Academic Resource CenterTime as an ARC Fellow boosts student confidence, encourages friendships and fosters lifelong learning habits. Senior Jackson Ezell reflects on his transformation as a tutor and the transformation of the center from Writing Center to Academic Resource Center.

See Details

Categories

- All

- Admission

- Athletics

- College Bound 2019

- College Bound 2020

- College Bound 2021

- College Bound 2022

- College Bound 2023

- College Bound 2024

- College Bound 2025

- Counselors Corner

- Episcopal Alumni

- Giving

- Head Of School

- Lower School

- Middle School

- Spirituality And Service

- Student Work

- The Teachers' Lounge

- Upper School

- Visual And Performing Arts